Determining the ideal counter-damage number - part 1

Finding the "sweet spot"

When the average juror walks into a courtroom, the juror’s concept of the value of a case is based on the extreme verdicts described in the media, the cherry-picked largest verdicts touted by plaintiff attorneys in their advertisements, and the often hefty amount of money requested by the plaintiff attorney at the trial. None of these numbers are helpful to the defense. Defense counsel must use every strategy available to reduce the impact of these multiple biased sources of information. Providing a counter-damage number is a strategy that often benefits the defense. In this article, we describe a scientific method of evaluating the utility of this strategy and for identifying the “sweet spot,” or the ideal counter-damage number for each specific case.

Plaintiff attorneys across the nation are brazenly making large demands, and then, if their demands are not met, going to trial and asking the jury for even more money than they originally demanded. One reason plaintiff attorneys feel comfortable requesting what some might consider outlandishly high damages is that they have been successful in receiving them. Often referred to as “nuclear verdicts,” verdicts considered disproportionately high compared to what would be expected given the economic damages or the plaintiff’s contributory/comparative fault for the outcome, are causing concern for defense counsel and insurers. The American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI) evaluated verdicts of over $1 million against defendants in the trucking industry and found that the average verdict increased from just over $2 million in 2010 to more than $22 million in 2018[i]. ATRI controlled for inflation and rising healthcare costs and still found that jury damages were increasing well above the expected rate. In several other areas of litigation, the number of “nuclear verdicts” has not increased, but the amount of money that jurors have awarded has increased significantly[ii]. According to TopVerdict.com, the top verdicts in the U.S. in 2012 and 2013 were just over $1 billion each year; while the top verdict in 2019 was $8 billion.

The concern is not simply with the “nuclear” verdict alone, but with the media attention to the verdict. The media tends to report outliers, in other words, extremely high civil verdicts; and it is rare for anyone in the media to report civil defense verdicts[iii]. Thus, the media attention to the few particularly large verdicts in a venue can cause community members to perceive large awards to be more common than they are. This effect occurs due to what psychologists refer to as “availability bias”[iv]. When determining the probability of an outcome, such as a multi-million-dollar verdict, individuals rely on information that is readily available in their minds, such as recent verdicts they have read or heard about. Large verdicts can then drive more large verdicts. Previous research has shown that the more common jurors believe large verdicts to be, the more likely they are to award large verdicts themselves[v].

While members of the media are likely unintentionally creating a false perception of the prevalence of high verdicts, plaintiff attorneys often do so intentionally through advertising. At the time this article was written, the homepage of the website for the large plaintiff law firm of Morgan and Morgan was plastered with “John Doe v. Insurance Company” claiming “What we won” as $4,999,117 with a pre-trial offer of $750,000 in an auto accident suit[vi]. By scrolling down the page, one may view the law firm’s claim of receiving “over 20 times more than what was offered” in “actual trial results” of $139,047,297 for a case with a pre-trial offer of less than $6.5 million, though it is not clear from the website what type of case had such a result. The verdicts that plaintiff attorneys tout on their websites, blogs, billboards, and commercials are also likely to increase community members’ perceptions of the prevalence of larger verdicts. Imagine a community member who has no involvement in litigation, having recently heard or read about a $5 million verdict in an automobile suit, who shows up to jury selection and finds that the plaintiff in an auto accident is requesting $5 million. While $5 million is well above the average verdict for an auto accident, the number is consistent with the most salient information the juror has for valuing such cases and the juror may not bat an eye.

Plaintiff attorneys are well aware that many jurors have no knowledge of what an average verdict is, or any idea of how to determine monetary amounts for noneconomic loss or punitive damages. Therefore, before going to trial, plaintiff attorneys are conducting focus groups or mock trials to determine the ideal ad damnum; in other words, the attorney identifies how much money he or she can request before losing credibility with the jury. Once the plaintiff attorney determines the highest damage number he or she can request, the ad damnum is mentioned early and often in trial so that jurors become desensitized to the large number and it serves as a psychological “anchor.” An anchor is a number that affects the judgments made by the jurors, solely due to the number being presented[vii]. Higher anchors provided by plaintiff attorneys can increase both jurors’ judgments of the defendants’ liability and the jurors’ determinations of damages[viii].

The Determination of Whether to Provide a Counter-Anchor

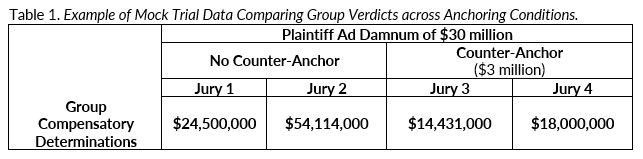

Just as plaintiff attorneys are performing pre-trial research to identify the highest ad damnum they can suggest, the defense is wise to perform similar pre-trial research to test the effects of a potential counter-anchor. Importantly, determining whether to provide a counter-anchor cannot be done by asking mock jurors to self-report what they would have done if they had heard a different presentation. In other words, a moderator cannot ask jurors at the end of a mock trial, “If, instead of saying nothing about the damages in the case, the defense had suggested that the damages should be no more than $1 million, what would you have determined in your damages?” Jurors often do not want to admit, or may not even consciously realize that they have been influenced by the plaintiff ad damnum or by a defense counter-damage number (or lack of one). To determine whether a counter-anchor would influence the damages, an experimental research design is required. This means that one group of mock jurors should be exposed to a mock trial in which the defense provides no counter-damage number and a separate group of mock jurors, who are matched to the first group, should be exposed to the same mock trial except that the defense provides a counter-damage number.

Of course, testing different conditions experimentally, if that requires running several mock trials, can be expensive. To efficiently and cost-effectively test different conditions, an online mock trial is ideal. Online mock trials save on expenses such as travel, catering and facility costs. Additionally, rather than having to perform a mock trial repeatedly over two or more days, with different jurors each time, as is necessary with an in-person project if you would like to test different conditions, an online project can be much more efficiently prepared with different conditions for testing. In an online project, attorneys create video-taped plaintiff and defense presentations. The videos can then easily be edited to create different counter-damages conditions. Additionally, online jury research more easily and cheaply incorporates larger samples of mock jurors. For example, 50 mock jurors can be recruited to watch videos of plaintiff and defense presentations, with half the sample viewing a video in which the defense suggests a counter-damage number and the other half of the sample viewing a video in which the defense suggests no number. Then, deliberation groups are formed from each condition and the damage determinations are compared.

By performing an online experiment, the defense can determine whether providing a counter-anchor will affect many aspects of the case, including compensatory damages, jurors’ determinations of liability or apportionment of fault, or the likelihood of a punitive award. All of the findings, once analyzed, will aid the defense in strategy for trial, not based on the intuition of the trial team, but on scientific findings.

[i]American Transportation Research Institute. (2020). Understanding the Impact of Nuclear Verdicts on the Trucking Industry. Retrieved from: ATRI-Understanding-the-Impact-of-Nuclear-Verdicts-on-the-Trucking-Industry-06-2020-2.pdf (truckingresearch.org)

[ii]Daly, A., & Mandel, C. (2020). Liability Litigation Trends and Practices. Sedgwick Institute. Retrieved from Sedgwick-Institute_Liability-White-Paper_052620.pdf

[iii]MacCoun, R. J. (2006). Media reporting of jury verdicts: Is the tail (of the distribution) wagging the dog? DePaul Law Review, 55, 539.

[iv]Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 207-232.

[v]Greene, E., Goodman, J., & Loftus, E. F. (1991). Jurors’ attitudes about civil litigation and the size of damage awards. The American University Law Review, 40, 805-820.

[vi]Morgan & Morgan website. Retrieved from: Morgan & Morgan - Free Case Evaluation - Get a Lawyer | Morgan & Morgan Law Firm (forthepeople.com)

[vii]Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124-1131. https://doi.org/10.21236/ad0767426

[viii]Chapman, G. B., & Bornstein, B. H. (1996). The more you ask for, the more you get: Anchoring in Personal Injury Verdicts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 10, 519-540.